– Ria S. Mazumdar(Guest Post)

A few months ago, an event was organized in the school where I work, wherein the students had to submit a rangoli design made on a piece of paper. Here in Bangalore, the pan-India background of the students is quite obvious. I was intrigued to see the regional touches in the Rangoli designs submitted.

Rangoli in West Bengal

In this pandemonium, my mind often races back to the happier times- to those of my childhood days.

As a young girl, I remember, the night prior to the Saraswati Puja, I was made to study for a couple of hours extra as the books would be resting at the deity’s feet for the next two days.

So, right after dinner, my mother would tuck her pallu in her waist and make me a loose batter made up of ‘Atop chaal’ ( refined rice) and water. She would then give me a piece of clean cloth, and with a twinkle in her eyes, she would say, “Go, now make something beautiful!” I would then sit and make the rangoli (or “Alpona,” as we call it in Bengali). Often this would continue till midnight. I would be accompanied by my Thamma, who would lie on the cot right next to me and narrate the stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata while I worked. Amidst the quietness of the night, she hummed through and the room would turn into a magical place with her vivid descriptions.

Also Read: The scroll painters of Naya – the village of myths and lores

Rangoli in South India

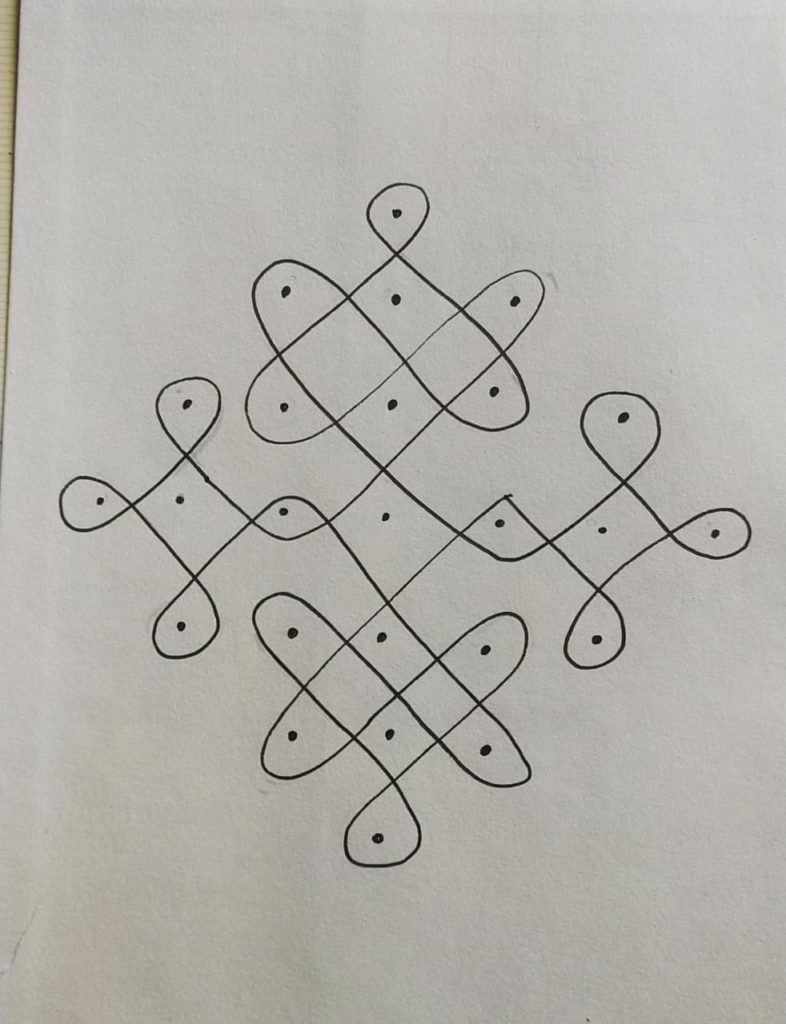

A few years later, when I was in college, I happened to visit Kerala and Kanyakumari for college excursions. The train was late, we reached the hotel at the crack of dawn. While on the way to the hotel, my curiosity was aroused again when I noticed ladies making rangolis at their thresholds. It was not wet; on the contrary, they were using some kind of a white powder. The rangolis looked very different too. There were no floral patterns, but an intricate pattern of dots and lines. The receptionist later explained that these were traditionally called Kolam in Tamil Nadu and Muggulu Rangoli in Andhra Pradesh. Rice flour was used to make these so that the ants and the birds didn’t have to go elsewhere looking for food. I was fascinated!

Kolams are still made at the thresholds of houses after the floor is wet wiped. In rural areas, much like that in Bengal, the floor is first smeared with cowdung. It is believed to have antiseptic properties.

Across India, special occasions are celebrated by laying down beautiful and colourful rangolis. In Bengal, we call it Alpona. It is called Aripana in Bihar, Kolam in Tamil Nadu, Muggulu rangoli in Andhra, Chouk Purna in Chattisgarh, Joti in Odhisha and so on.

But how did it all start?

To assign this practice to the recent past would be an anachronism. There are myriad stories and anecdotes to support the creation of such rangolis.

Thamma once told me that the first Rangoli ever was made by Lopamudra, the wife of Agastya Muni. She wanted to help her husband in his daily rituals and decided to decorate the Yajnakunda. So, she invoked all the five elements from nature and, therefore, derived red colour from the fire, white from the wind, black from the soil, green from the water and blue from the sky. That’s how the first-ever rangoli was created.

One more story from Mithila, Bihar, mentions that King Dhrupad was ecstatic when Ram wed Sita and commanded the royal servants to decorate the whole palace with ‘Aripanas.’

Another story from Southern India mentions how the Gopis drew kolams to drown their sorrows when Lord Krishna left Vrindavan.

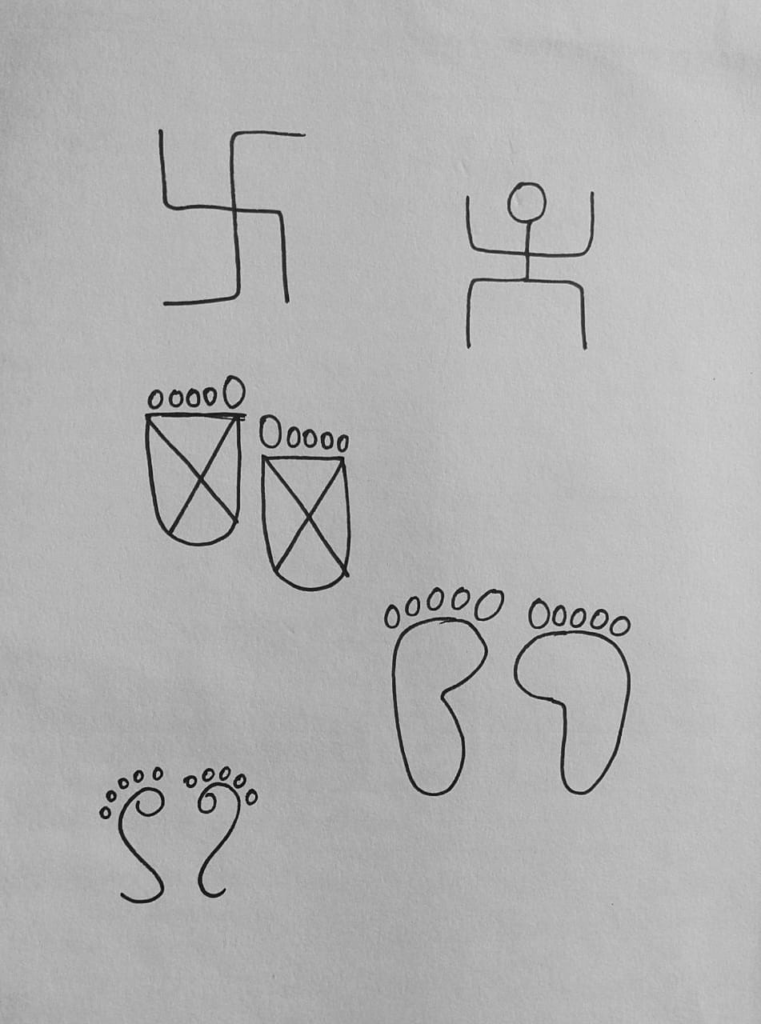

Some of the common motifs used in such rangolis are also very riveting. Considering the fact that during ancient times, the means of communication were very limited. Yet, there were many similarities in the Vedic symbols used in the designs pan India.

Such designs became absorbed into tribal households as well. One could find evidence of these symbols on the walls of the mud houses in many tribal villages across the country as well.

The practice of drawing threshold rangolis resonates with the idea of “Vasudaiva Kutumbakam”- the entire universe is a single family. The designs are primarily symmetrical, which portrays the idea of Shiva and Shakti and idealizes universal balance. Rangolis are made to drive away evil spirits and channelize positive energy to promote a sense of unity and peace.

I genuinely feel that we all should realize the significance of these traditional practices. And arise from “me and you” to “us.”

Trivia

In several Asian cultures, we find a prevalent spiritual symbol called ‘Mandala.’ It is also found in several monasteries in Sikkim. Mandala directly translates in Sanskrit to a round object. It is believed that as one progresses from the outer core of the mandala towards the centre, all his sufferings transform into joy.

About Ria S. Mazumdar

Based in Bangalore, Ria is an educator by profession, artist and singer by passion. A true Bong at heart- that kind of a person who would choose fuchka over panipuri, polau over biryani and ‘mamlet’ over “omlette”!